From secret meetings to public exhibitions: A new era of environmental activism

Environmental activists have enjoyed more freedom since the “opening up” of the country five years ago, but challenges remain – especially regarding access to information.

It was not the Sihasana (lion throne) or the poorly lit betel spittoons that drew people to Yangon’s National Museum early last Sunday morning. The 150 people who visited that day were there to see poet Maung Sein Win, well-known author Ju and political scientist Minyin speak about the Ayeyarwady River and the geopolitics of Chinese dam construction.

The event, which was held in the museum’s auditorium, was organised by the Ju Foundation, and included an exhibition of photographs of the Ayeyarwady and its natural surrounds as well as paintings by children from families that have been resettled as a result of the Myitsone dam construction project in Kachin State. On the floor of the auditorium, a large map showed communities that will be affected if the dam construction, suspended in 2011 by then president U Thein Sein, continues.

“We have organised this event because it is a crucial moment,” said event organiser Myint Zaw, an environmental activist and recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize 2015. “In a couple of weeks the Investigation Commission for Hydropower Projects will release its first report. We will then hopefully know more about the government’s stand on the Myitsone project.”

It is a sign of the times that such an event, attended by local media, civil society activists and members of the general public, took place in the prestigious halls of the National Museum. When Myint Zaw started campaigning against the Myitsone dam in 2009, he and his fellow campaigners would meet at small art galleries, such as Gallery 65 in Yangon. Exhibitions acted as a pretext to talk about environmental issues, like the potential resettlement of 18,000 people from nearly 50 villages, and the impact of Myitsone on downriver communities – though they had to be careful what they said, and often spoke in “code”.

Myint Zaw and his colleagues took great risks, always afraid that spies of the military regime may have sneaked into the crowd. “Until recently, speakers would meet before an event and ask the organisers about the crowd. With that information they then would decide on how freely they could speak,” said Myint Zaw. “This Sunday, none of the speakers was asking about the crowd. I take that as a promising sign regarding the freedom civil society nowadays enjoys in this country,” he added.

His statement contrasts palpably with outside assessments, such as that of US watchdog Freedomhouse, which scores countries from one (most free) to seven (least free). In 2016, it scored Myanmar six for political rights and five for civil liberties. According to Freedomhouse, the situation for civil society in Myanmar remains dire, even five years after the country’s first social and political reforms and one year after the country’s first democratic government for more than 50 years was elected. It labels the country simply as “not free”.

For German political scientist Julian Kirchherr, who is currently completing his PhD at Oxford University, the rating does not give an accurate picture of civil society in Myanmar. As part of his research on conflicts related to dam projects in Myanmar he interviewed more than 40 civil society activists throughout the country. His conclusion: “There is very little left [that] local NGOs in Myanmar can’t, or won’t, do these days.” Kirchherr explains that environmental activists – contrary to the popular belief – were already active under the military regime, though they operated clandestinely. The campaign against the Myitsone Dam, for example, dates back to 2004.

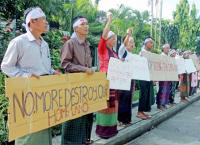

“Activists would disguise classical protests under the military regime,” he said. “Demonstrations against the Myitsone Dam would be framed as mass prayer ceremonies in support of the Ayeyarwady River.” During those years of secrecy and fear, nobody dared to imagine that an event like last week’s could take place in public at the National Museum.

Mirco Kreibich, head of German independent political foundation Heinrich Boell Stiftung’s Yangon office, shares the optimism of Myint Zaw and Kirchherr. “When you look at the situation in neighboring countries like Laos, Cambodia or Indonesia, Myanmar has become something of a paradise for activists,” he said. HBS was present in Myanmar even before NGOs were allowed to work in the country. The foundation started conducting democracy and environmental justice activities from its Bangkok office in 2004, through fellowships given to local students for studies abroad. In 2012, after the “opening” of the country, it established a Yangon office.

So far, Kreibich said he has been able to work without restrictions, but he points to challenges that remain. “The representatives of the government are hardly accessible for us,” he said. There are also the so-called “iron rules” which forbid MPs from openly talking to media and oblige them to seek prior permission before attending events hosted by civil society organisations. For Kreibich, this poses something of a contradiction, as civil society was one of the biggest supporters of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her party before the 2015 elections. Another concern, Kreibich says, is gaining access to remote regions controlled by the military. Large parts of Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states remain off-limits to foreign organisations, particularly regions in which logging and illegal trade are known to take place, and where many of the new dams are supposed to be built. HBS gets much of its information from its fellows, many of whom returned to their hometowns after completing their studies and provide the foundation with first-hand information.

One of them is Shining Nang. She grew up in Mong Pan, a small village in Shan State, and left the country when she turned 22 to study international development in Thailand, where she specialised in the social and environmental impacts of dams. After further studies in the Philippines and Costa Rica, she returned to her hometown in 2014 to found the Mong Pan Youth Association. Her aim was to mobilise youth in her village and surrounding communities against the Mong Ton dam (previously known as the Tasang dam) – the largest dam ever planned in mainland Southeast Asia and the largest of five dams to be developed on the Salween River. A 7000-megawatt, US$6 billion project, financed by a consortium of Chinese, Thai and Myanmar developers, the dam was expected to force 12,000 people off their land. Not unlike the Myitsone project, 90 percent of the electricity generated by the dam would go abroad – to Thailand and China – with only 10pc staying in Myanmar. Shining Nang and her group conducted research on the ongoing of the project on the ground, organised spiritual protests with Buddhist monks in front of the blocked area and collected signatures for petitions.

“Today, one of our problems as activists is that we don’t have access to the construction site. So it’s very difficult to know what exactly happens on the spot,” said Shining Nang. Large parts of the area around the Mong Ton dam were fenced off by the military and neither the displaced farmers who originally worked on the land nor local or international NGOs have access to it. Only through speaking to domestic workers hired for the project has Shining Nang found out that test drillings and measurements are currently being done. When her group organises meetings with local communities to raise awareness about the dam, the military is often present and their activities are observed and documented.

Local authorities even warned Shining Nang against using the words “human rights” in the title of one of their events.

“I said to him, ‘This is our right now!’ but he refused to [allow] it. What we experience every day is that, even though we now can gather and publicly speak about social and environmental issues, the political changes at the national level have not yet trickled down to the regional level,” said Shining Nang.

While challenges remain for grassroots environmental activists on the ground, their outreach activities have increased and are having a greater impact. They have built stronger networks between national and international actors, and in July last year 122 concerned groups all over Myanmar issued a joint statementagainst all planned dam projects along the Salween River. It was an unprecedented closing of ranks for Myanmar civil society. In September last year, a petition with 30,000 signatures was sent to the Australian company charged with the Environmental Impact Assesment (EIA) for the Mong Ton dam. The EIA finally was postponed and its continuation remains in limbo.

The funding available for civil society activities has also increased significantly.

“One can see the impact of money when comparing the older Myitsone dam campaign against the Mong Ton dam campaign,” said Julian Kirchherr. “While the Myitsone campaign was always short of cash, this is clearly not the case in the Mong Ton campaign.”

On September 28 the group Action for Shan State Rivers launched a costly, 30-minute documentary film, which was partly filmed with drones, to show the beauty of the region threatened by the dam. The film is available not only in Myanmar language but also in Thai and English, and to date has been viewed by over 3000 people on YouTube.

The new realities of civil society activism were highlighted by Bo Bo Lwin, founder of the Kalyana Mitta Development Foundation (KMF), a social and environmental youth network operating throughout the country. When he first started his organisation in 2008, their meetings would take place in dusty teashops, known for their absence of military spies. There was no office, no address and they would carry all of their documents around with them in backpacks. Annual gatherings of members were held in the woods, disguised as trekking events. Today, KMF employs 34 staff across its three offices, and Lwin regularly flies out to London for donor meetings. “I would never want to miss the freedom we have gained these last years,” he said. “But sometimes when I run from one meeting to another or when I am pinned down for weeks to write an annual report, I look back slightly nostalgicly to those adventurous founding days.